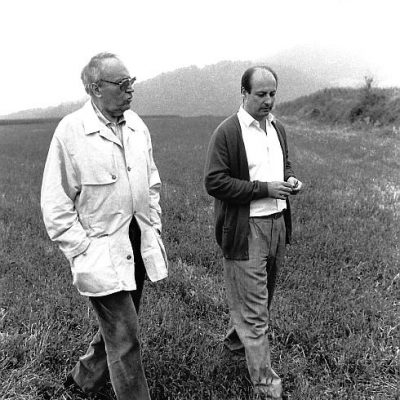

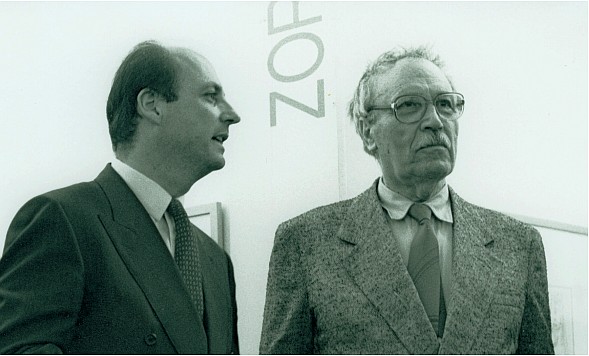

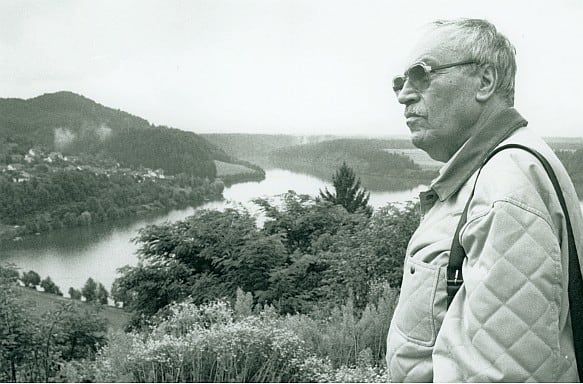

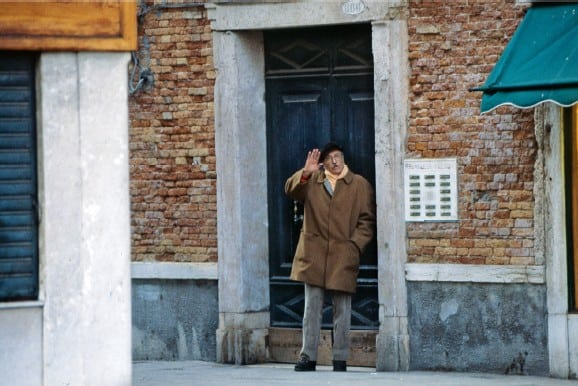

Another picture of my life will then perhaps once again appear before my eyes, a picture that continues to accompany me to this day: the aged artist Zoran Music in his Parisian studio or on the balcony of his Venetian palazzo.

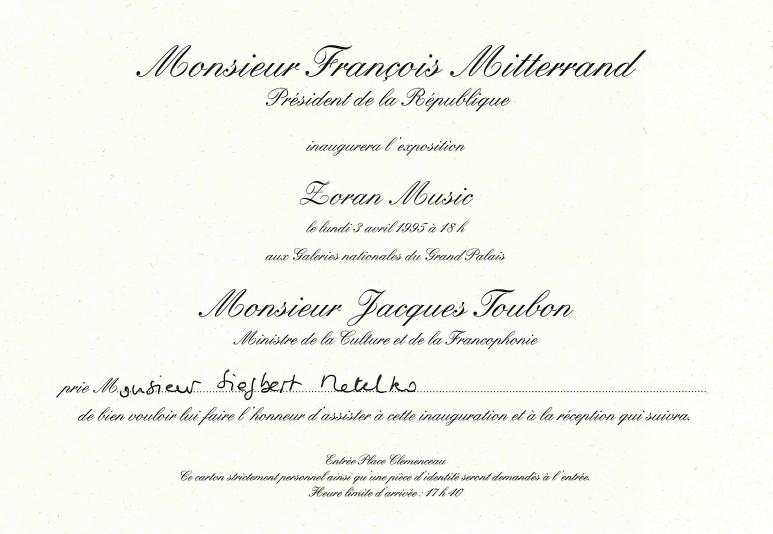

And the moment when President Mitterrand arrives in front of his apartment in Paris to drink coffee. By the way, years later, Mitterrand was supposed to stage his own dying as if he wanted to try the Egyptian Book of the Dead as a private guidebook: his ultimate trip to Upper Egypt, where he originated in the Cataract Hotel – Agathe Christie’s novel “Death on the Nile” in this environment. – waiting for his last hour will remain in memory.

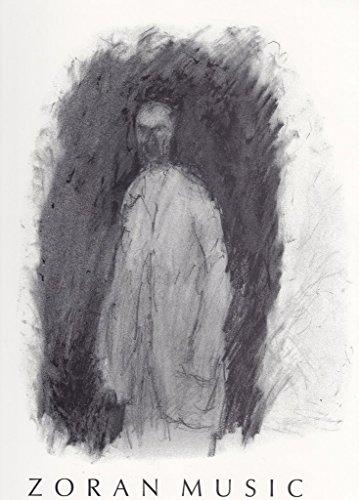

Back to Zoran Music. Music was a respectful figure, nothing could shake him more: he had faced death for months every day.

Music allowed dying and death into the picture. The close proximity of the death music has experienced them, not in the provocative tickle of Russian roulette, which makes death as a calculable risk to parlor games, but in existential experience.

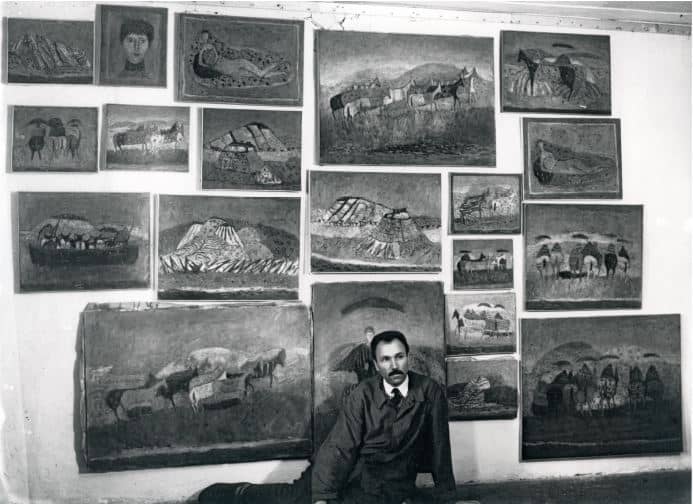

To be more precise, he had looked into the eyes of thousands of corpses, piled up like firewood on hills in the snow outside the crematorium of the Dachau concentration camp. If a pile was burned, the next delivery came. Music secretly drew these mounds, if he could find a piece of paper. And even before they had deported him to Dachau, he had to witness the dying: In the interim storage they took SS-minions day after day from inmates to murder them. Music remained to testify.

In a text to the exhibition in the Gallery Naviglio in Venice in 1949, the Liberated writes:

“Finally the big light, finally the sun, infinite sky to the low horizon of the lagoon, all that belongs to me, here I can breathe freely … Is it really true that no one is watching me? Is it true that I am free to paint? Was it that I did not need to hide the drawings, fold them up fourfold or cut them to pieces? “

From a few sentences speaks the happiness of a person who has lived in a world beyond imagination, in a world where DEATH is “normal”, where the horror of everyday life was.

Was? Or is?

From then on, Music looked at nature from this point of view. The lovely hills of Tuscany seemed to him like makeshift covered mounds, skeletons.

And again and again, the silent cry from the open mouths of the dead pressed on him: “We are not the last ones, non siamo gli ultimi …”

The artist will never cease to articulate this cry in his paintings until his own death.

Even decades after the real horror pictures, the night faces of the deadly eclipse caught up with the painter again.

And yet, Zoran Music rested unshakably within himself. Where did he get his fortitude, I often wondered. Perhaps he had become strong because he saw many deaths in his life and therefore died in advance many deaths in advance. Perhaps it was similar to Dostoyevsky, arrested as a revolutionary-inspired young poet, and dressed in death-clothes, tied to a post, standing in front of a firing squad. A mock execution. Then the pardon was read to him and the sentence: exile to Siberia. Under this impression he became a prophet among Russian poets …

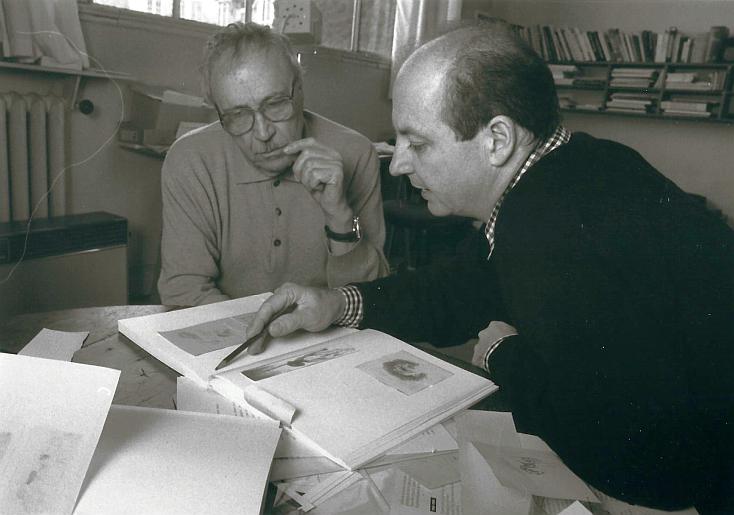

In more than 300 pages of notes and notes from our conversations, I have pulled out those that concern the leitmotif of his immense work, the “death pictures”. Music, however, has met demand that is made to anyone in excess; “THINK OF DEATH!”. The consciousness of extinction and transience shapes up to the last pictures of the artist a pictorial atmosphere of the colored concealment and the figurative volatilization.

“We are not the last …” In 1992, I wrote a text for an exhibition by Zoran Music, at the time of the horrors of the war in Bosnia. It is still valid today when we think of Aleppo, Mosul or the global terror.

Siegbert Metelko, 2016

Siegbert Metelko je bil ozek spremljevalec Zorana Mušiča

STRUKTURNE SLIKE K ZORANU MUŠIČU

Manfred Pichler je fotograf in je objavil te strukturne slike. www.pichler-fotokunst.at