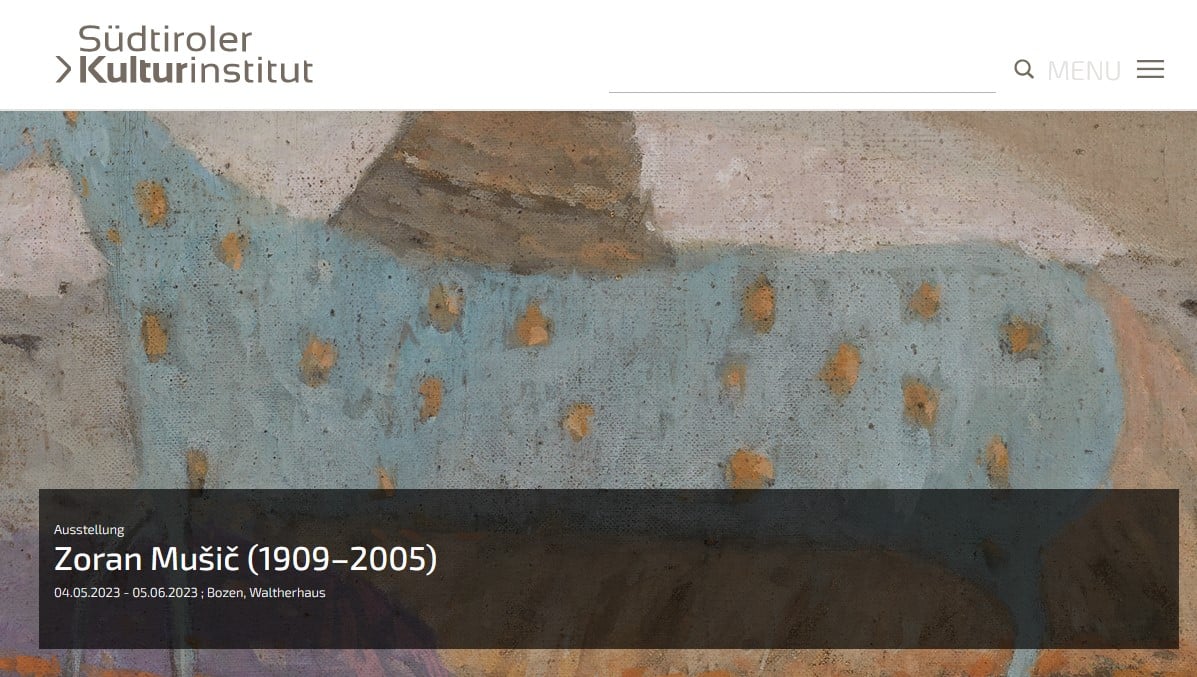

Zoran Mušič exhibition in Bolzano

04.05.2023 - 05.06.2023 | Bolzano, Waltherhaus

The South Tyrolean Cultural Institute opens the exhibition on Zoran Mušič (1909-2005) curated by Wilfried Magnet and Siegbert Metelko on Thursday, May 4 at 6 pm in the Waltherhaus in Bolzano.

Anton Zoran Mušič was born in 1909 in Bukovica near Gorizia. He is a world artist in the Europe of the 20th century, has experienced all the turmoil of the last century. He is internationally recognized, his works are in important worldwide collections.

Zoran Mušič grew up in a trilingual area of the Habsburg Monarchy, Slovenian was spoken in the family, his father was a school principal, his mother a teacher. After the end of World War I, the family moved to Carinthia, where the father got a job teaching Slovenian students.

Zoran’s special closeness to the Carinthian Slovenes is also closely connected with his school days in Griffen (birthplace of his friend, the future Nobel Prize winner Peter Handke) in the district of Völkermarkt.

He completed his art studies in Zagreb in the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes from 1930 to 1934, after which he worked as a freelance artist , with longer stays in Spain and Dalmatia. Here he created his first landscape paintings, and from then on the Karst became a central theme of his painting.

At the beginning of October 1944, Mušič was arrested by the Gestapo in Venice because he was in contact with the anti-Nazi resistance. Because of his painting and drawing in Venice, he was suspected of being a spy. He was deported to the Dachau concentration camp, where he survived the end of World War II. Mušič then settled in Venice, which, along with Paris, became his preferred place of residence.

Several times he participated in the Venice Biennale and the documenta in Kassel and received numerous international awards. His subjects are the barren landscapes of Dalmatia and central Italy, views of Venice and Paris, in between portraits and scenes from the everyday life of peasants and fishermen. As a technique he preferred oil on canvas, besides gouache, watercolor and colored pencil and again and again printmaking. A special artistic achievement are his memories of Dachau, which he processed in the impressive series “We are not the last” in various techniques in the 1970s.

At his death in 2005, Music was one of the most important European artists, whose works are shown in the leading museums and galleries in Italy, France, Slovenia and Switzerland, but also in Germany and Austria.

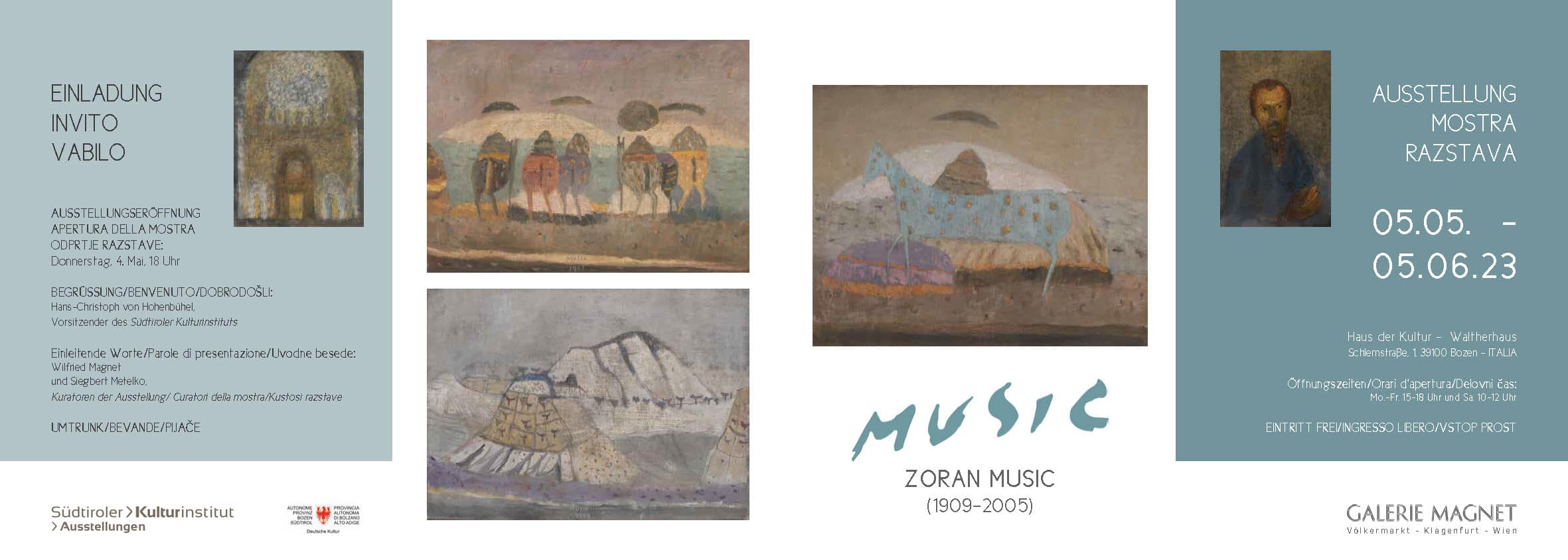

Image: Zoran Mušič (1909-2005), Cavallo azzurro, 1950, oil on canvas, 59,5x80cm, back signed dated titled, photo gallery Magnet

Place: House of Culture – Waltherhaus, Via Sciliar 1, Bolzano

Opening: Thursday, May 4, 2023 at 6 pm

Welcome: Hans-Christoph von Hohenbühel, Chairman of the South Tyrolean Cultural Institute

Introductory words: Wilfried Magnet and Siegbert Metelko, curators of the exhibition

Hours: May 5-June 5, 2023, Mon.-Fri. 3-6 p.m. and Sat. 10 a.m.-12 p.m. Free admission, closed holidays.

Speech on the occasion of the exhibition opening by curator Siegbert Metelko:

“There are encounters that point one’s life in a new, previously unknown direction. So it was in 1986, when I was confronted with the paintings of Zoran Music in the Museo Correr in Venice: for the first time I saw the terrible visions of the series “Non siamo gli ultimi”, the painted mountains of corpses, in which the artist commemorated the dead concentration camp comrades in the Dachau concentration camp in a mourning work that was never finished.

As a young man he had been deported there, arrested in Venice, and after an internment in the Trieste concentration camp Risiera di San Saba, abruptly torn out of a promising artistic career.

By an irony of fate, Music fell into the hands of his pursuers right in front of the portal of Palazzo Balbi-Valier , where he would live much later with his congenial wife Ida Barbarigo.

Behind this fateful portal, the couple would host both their friend, French President Francois Mitterrand, and accompany him until hard on the brink of his death. What Zoran Music had to watch, the frozen dead under a shroud of snow, the hanged on the gallows, will give him nightmares; even the later brilliant successes in Paris, in Germany and in Italy, culminating in the great retrospective at the Grand Palais, will not change that. Music paints a requiem for human civilization, whether in serene Paris, whether in the Karst or on his altane in Venice.

Zoran Music had been expelled, so to speak, from the paradise of his childhood and youth, and no way back was open to him, except in the temporary retreat under the golden mosaics of San Marco, whose diffuse otherworldly glow he tries to capture in late paintings. Music grew up in the Collio, the idyllic landscape north of Gorizia/Nova Gorica. He had already had to leave the idyll with his parents once, in the course of the First World War, when an absurd front line ran through the vineyards.

He spends formative months in Griffen, in southern Carinthia; in old age he was allowed to enter his former nursery, shortly before the temporary domicile was demolished.

In this life of escape from the hells of the 20th century, in the imprisonment in Dachau, but afterwards in the contemplation of the rediscovered beauty of the Old World, already thought to be completely lost, he became the painter of that mythical continent we call Central Europe. This Central Europe is the synthesis of the traditions and cultures of Europe.

He had already discovered Spain in the 1930s, where he studied the works of Velazquez and Goya. Both artists had an unmistakable influence on his own painting; they taught him to see the world from a supra-temporal perspective: Velazquez as the painter of Hispanidad, of the Spanish ethos, who influenced the cultural history of Central Europe through the courts of Madrid and Vienna; Goya as the painter and chronicler of the disasters of the Napoleonic wars.

Nothing could be as it was when Zoran Music was freed from the concentration camp in 1945. Yet he was searching for his roots, perhaps for healing of a trauma that ultimately could not be healed. Because “non siamo gli ultimi” – “We are not the last”: the silent lament of the dead will accompany him, even as he seeks to gain distance.

In Venice he marries Ida Cadorin, spiritual heiress of a legendary dynasty of painters who will call themselves “Barbarigo”, Paris becomes his second home next to Venice, the landscape of the Karst and Dalmatia reminds him of the Mediterranean impressions of his childhood. Today, if you drive through the Karst above Trieste, away from the highway, you can still meet them, the half-wild horses galloping on the dry ground, the “Cavallini”. They run through the area as if over a mosaic of white stone chips, with a kind of thoughtful humor Zoran Music looks at them and paints them in their cheerful lack of history.

All too often, however, the image transforms before his eyes. Then the white rubble reminds him again of the white skulls of the dead of Dachau and the little horses remind him of an unattainable feeling of freedom, a freedom that he knows is constantly threatened. Because what has happened once will have to be repeated again and again.

There is no optimism in history for Music, irrefutably experience remains.

Since 1988 I had closer contact with Zoran Music. I remember the many hours we spent in his Paris studio and his magnificent house in Venice, the stories from his biography, which virtually exemplifies the Central European tragedies of the 20th century. In his domain he always presented himself as a sovereign, self-critically he sometimes rejected impressive sheets and sketches, he had to be persuaded not to destroy anything.

Standing in the midst of his work in his floor-length white robe, he was nevertheless pleased when people took an interest in his work. He knew that he did not want to belong to any of the artistic trends of his era and did not care in the least whether his works corresponded to a trend, whether they would ever be marketable. His fame proved to be time deprived.

Which is also true of the paintings of Ida Barbarigo, whose series of portraits of President Mitterrand reveal an essence more to be understood from esotericism than from the day-to-day politics of his time in office.

In this field, terms like “modernity” or “avant-garde” lose all meaning. Both of them look at the world “sub specie aeternitatis”, from eternity.

When Zoran Music draws and paints the barks on the Venetian zattere, when his gaze lingers on a window in the red façade of a Venetian house, when he paints the rose in the side aisle of San Marco, he conjures up a Venice beyond space and time.

There is a fascination that emanates from this work that one has to make an effort to understand. Those who do not get involved with the personality of the Master will not find access to his world. In a conversation with Jean-Marie Drot, he once lifted the veil of discretion and confessed, with regard to his drawings from Dachau, which he had made at the risk of his life: “I drew as if in a trance. I was dazzled by the enchanting magnificence of these fields of corpses. From a distance they appeared to me like white snowfields, like silvery reflections on mountains, or again like the flight of seagulls settling on the lagoon, against the black background of a thunderstorm over the sea …” And further: “Not at all as a reaction against the horror I rediscovered the happiness of childhood: small horses, landscapes and women of Dalmatia. They were already there before. It was just that afterwards I saw them differently. After the vision of these corpses, stripped of all external attributes, of all superfluous things, freed from all hypocrisy and from the distinctions of rank with which people and society adorn themselves, I believe I have discovered the terrible and tragic truth that I was given to know…”.

Thus, Zoran Music and Francois Mitterrand walked along the Zattere, two people united by an inkling of the great mystery beyond history. That I was able to accompany Music for a stretch of his life is a privilege of a lifetime.”